Overview

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestionsObjectives

- What are Jupyter Notebooks?

- What can Jupyter Notebooks be used for?

- Get an idea of the purpose of Jupyter.

- See some inspirational Jupyter notebooks.

Jupyter Notebooks

Some history

- In 2014, Fernando Pérez announced a spin-off project from IPython called Project Jupyter, moving the notebook and other language-agnostic parts of IPython to Jupyter.

- The name “Jupyter” derives from Julia+Python+R, but today Jupyter kernels exist for dozens of programming languages.

- Galileo’s publication in a pamphlet in 1610 in Sidereus Nuncius, one of the first notebooks!

What are Jupyter notebooks?

- A literate programming tool.

- Code, text, equations, figures, etc. are interleaved, creating a computational narrative.

- “an environment in which users execute code, see what happens, modify and repeat in a kind of iterative conversation between researcher and data”

Case examples

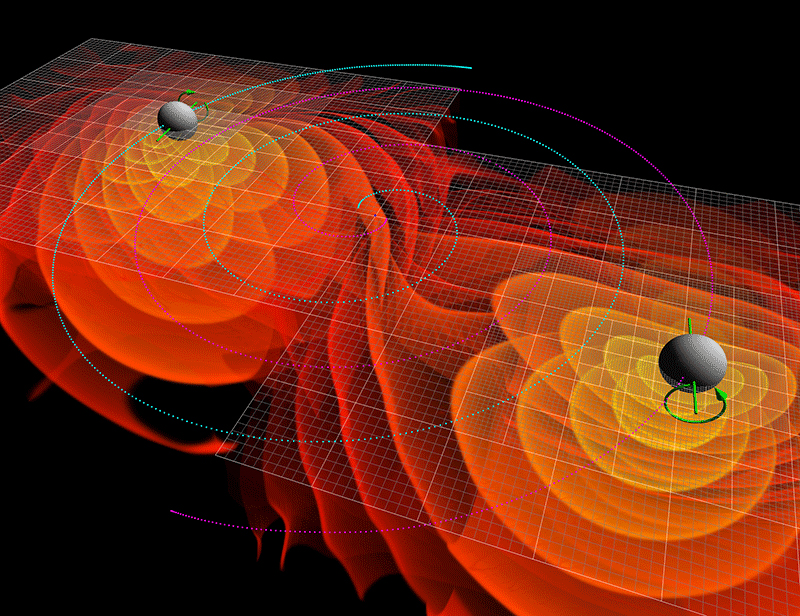

Gravitational wave discovery

Let us have a look at the analysis published together with the discovery of gravitational waves. This page lists the available analyses and presents several options to browse them.

- A quick look at short segments of data can be found at https://github.com/losc-tutorial/quickview

- The notebook can be opened and interactively explored using Binder by clicking the “launch Binder” button.

- How does the Binder instance know which Python packages to load?

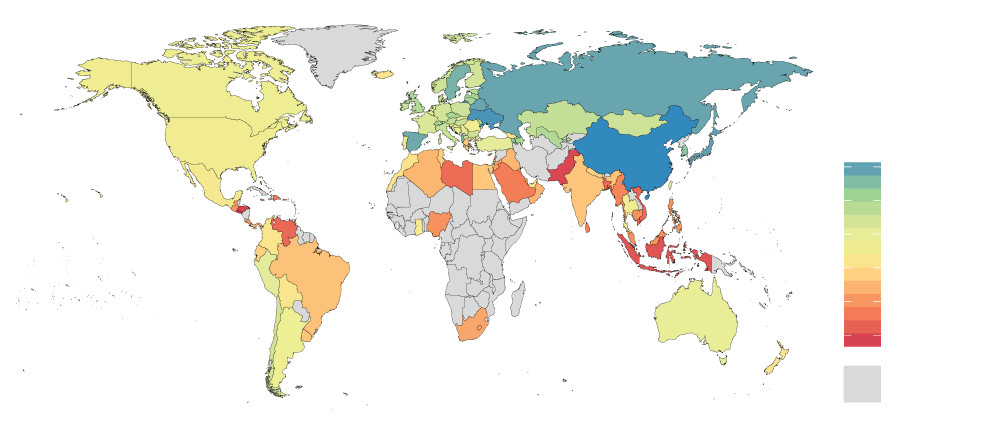

Activity inequality study

Researchers in the Stanford Activity Inequality Study measured daily activity from cell phone tracking data for over 700,000 users in different countries across the world.

- All data and notebooks are available at https://github.com/timalthoff/activityinequality

- Even without a “launch binder” button, the notebooks can still be

launched on Binder

(you may see an error “missing R kernel” because a file

runtime.txtis missing - more about that later) - Do you see any potential problems in recreating e.g. fig3bc?

More examples

For further inspiration, head over to the Gallery of interesting Jupyter Notebooks.

Common use cases

- Really good for linear workflows (e.g. read data, filter data, do some statistics, plot the results)

- Experimenting with new ideas, testing new libraries/databases

- As an interactive development environment for code, data analysis and visualization

- Interactive work on HPC clusters

- Sharing and explaining code to colleagues

- Teaching (programming, experimental/theoretical science)

- Learning from other notebooks

- Keeping track of interactive sessions, like a digital lab notebook

- Supplementary information with published articles

- Slide presentations using Reveal.js

Pitfalls with notebooks

- Less useful for large codebases. They don’t promote modularity, and once you get started in a notebook it can be hard to migrate to modules. Once lots of code is in notebooks, it can be hard to change to proper programs that can be scripted.

- Less useful for non-linear code flow.

- They are difficult to test. There are things to run notebooks as unit tests like nbval, but it’s not perfect.

- Notebooks can be version controlled (nbdime helps with that), but there are still limitations.

- You can change code after you run it and run code out of order. This can make debugging hard and results irreproducible if you aren’t careful. We recommend to run all cells before sharing notebooks with others.

- Notebooks aren’t named by default and tend to acquire a bunch of unrelated stuff. Be careful with organization!

- See also https://scicomp.aalto.fi/scicomp/jupyter-pitfalls.html

- You cannot easily write a notebook directly in your text editor (but you can do that with R Markdown).

Key Points

Jupyter is an open-source, interactive web tool allowing researchers to combine code, output, explanatory text and multimedia resources in a single document.